Of Forests and Owls

Fri, October 18, 2024

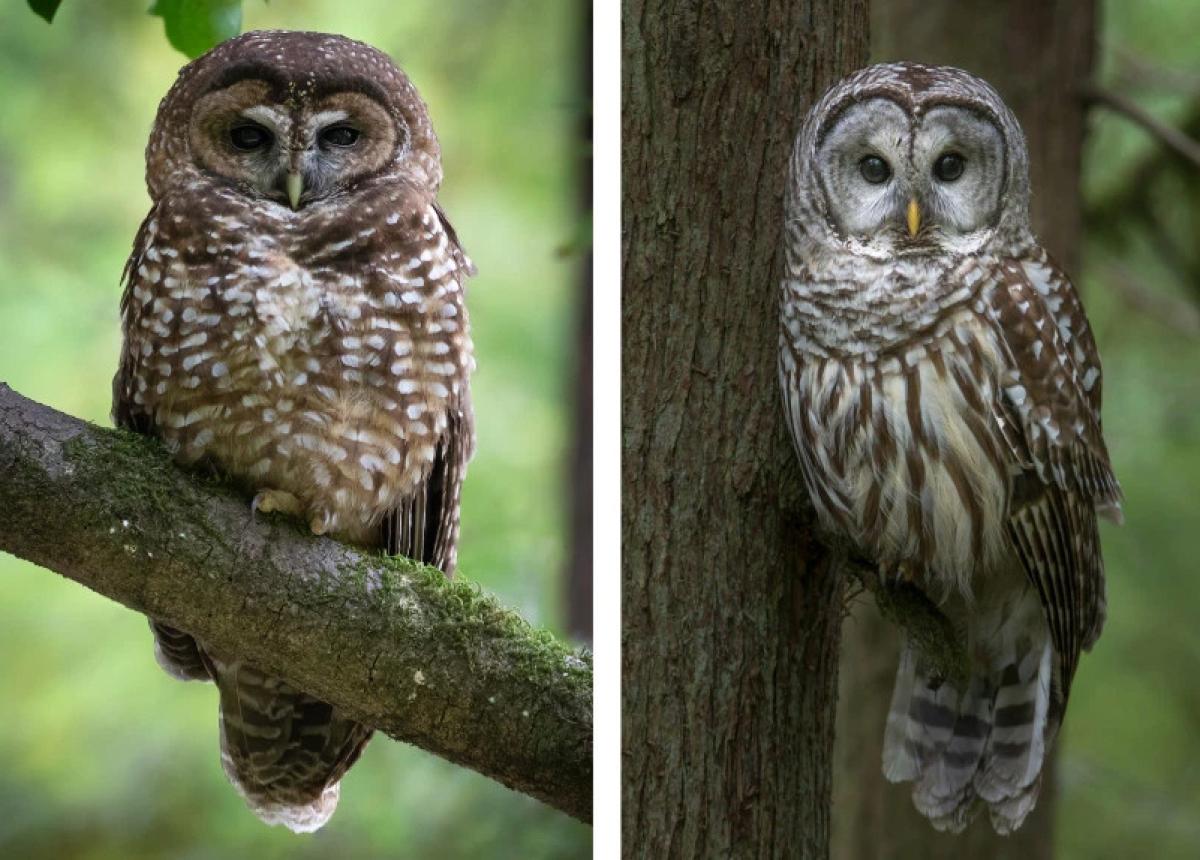

A watermelon-sized owl with dusky brown breast feathers sporting cream-colored spots lets out a “woot wootwoot wooo” identifying it as a spotted owl calling for a mate. A necessary action for its reproduction, but also a dangerous one. An intruder lurks nearby. The intruder, a larger bird by 20%, hears the call and responds with what sounds like “whoo cooks for youuu” in a muffled tone and takes flight. The cream-colored breast with vertical brown streaks and distinctive call identify it as the notoriously aggressive barred owl. They are even known to attack hikers, stealing their hats!

The second owl lands 20 yards away from the first and begins to pick a fight. The spotted owl is no coward so it answers back and the two fly at each other… Bang! They bump breasts, the larger owl bowling over the small one. This is repeated two more times before the smaller owl has had enough and takes off looking for a safer forest. But does any refuge exist?

While dramatized, this account is probably not far off the mark, as barred owls colonize new regions and push out the indigenous spotted owl. The barred owl is a fairly recent occupant of the Pacific Northwest, traveling here on the heels of modern western settlement. It is different from the spotted owl because it is a generalist, meaning that it eats just about anything. This includes other owls such as the saw whet, western screech, and spotted, as well as rodents, amphibians, and even crawfish! In contrast, the spotted owl is a specialist, primarily eating northern flying squirrels and dusky-footed woodrats. As a result, 10 or more pairs of barred owls can occupy the same area that would only support 1 pair of spotted owls! Another result is that there is nowhere that a spotted owl can live that a barred owl cannot. Barred owls occupy a wider range of habitat than the spotted owl, so there is no stable refuge for the spotted owl. The outcome, if we decide not to protect spotted owls from barred owls, is that the spotted owl will be driven to extinction. The spotted owl is already more or less non-existent in many parts of the Pacific Northwest.

Habitat for Northern Spotted Owls is the touchstone issue that halted logging on federal lands in the Pacific Northwest in the mid 1990’s while the Forest Service developed a credible plan to manage viable spotted owl populations. The resulting plan is called the Northwest Forest Plan, which reduced timber available for harvest by >50%. As we learned from research stimulated by these events, the spotted owl is a mature and old-forest specialist needing high canopy cover for dispersal (>35%) and foraging (>50%).

At the same time, the US Forest Service has historically suppressed wildfire in forests that used to burn frequently from Native American burning and lightning strikes. The frequent fires used to maintain a more open forest structure with less fuel where most of the large and old trees would survive from one fire to the next. After a century of suppressing fire, we created the fuel-heavy forests we are now trying to manage so they do not burn so severely that they kill most of the old trees. The younger trees in these forests also reduce the vigor of old trees by competing for water and by shading and killing lower to mid-crown branches making them vulnerable to insect attacks.

Figures 1-4 above: These figures show a progression of forest ingrowth from low-density frequent-fire ponderosa pine to steadily increasing tree density. Note the large pine in figure three in the right third surrounded by young trees. The other large pines in the photo are hard to find because they are obscured by small trees. The last photo is of a forest that has completely filled in with younger trees that are now large enough to kill the understory shrubs. Photos by Russell Kramer

Figure 5: A cluster of old pines to the left are becoming overgrown by competing trees. Photo by Russell Kramer

The rub is that with fire suppression, some of the canopy of these forests has now filled in enough to become marginal spotted owl habitat where none existed before.

Enter the controversy. On one hand, we have a rare owl, likely going extinct, that needs as much barred-owl-free old-forest habitat with dense canopy as it can find. On the other hand, we have increasingly large centuries-old pines in danger of dying in a fire or from water stress and insect attack. It appears that reducing forest density will harm the spotted owl, but doing nothing risks losing it all because the spotted owl cannot survive in a forest of dead trees. Is this a zero sum game?

Figure 6: Overstory tree mortality is high in this area of the Copperfield Fire 2024. High fuel loads and high canopy cover contribute to old-tree mortality in such forests. Many of the trees with needles are heavily scorched and will die in the next few years. Photo by Russell Kramer.

Figure 7: Increased tree density leads to water stress. Pockets of many dead trees are apparent in this photo. Photo by Russell Kramer

This is exactly the question we have been tasked with in our work on the former Klamath Tribes Reservation that the Tribes now co-manage with the US Forest Service. Can we write a prescription that forest equipment operators can use to save as many big old trees as we can while also preserving meaningful habitat for the spotted owl?

After spending a week in the field walking the forests, we think there is a way forward. There are many pockets of very dense trees with few to no old trees in them. We think we can retain 30 to 50% canopy cover by leaving some of the patches where they do not endanger many old trees and where we can leave dead trees as habitat. The old trees are of sufficiently low density that we can remove all competing trees out to one crown diameter around them without overly compromising the canopy cover. Now we need to figure out if we can remove enough trees to pay the forest workers to do the work…

*Title Photos are from: sierraclub.org/san-francisco-bay/marin/ endangered-northern-spotted-owl